A Historical and Analytical Inquiry

Introduction: A Nation Between Promise and Reality

The history of religious minorities in Pakistan is marked by a steady erosion of citizenship, shrinking constitutional protections, and an increasing push toward religious homogenization. At its creation in 1947, Pakistan inherited a deeply plural social landscape that included Hindus, Sikhs, Christians, Parsis, and Ahmadis—particularly in Sindh, Punjab, and East Bengal. Yet, over nearly eight decades, this pluralism has gradually diminished.

What has unfolded is not a sudden rupture but a long historical process: one shaped by discriminatory laws, institutional bias, social exclusion, and recurring episodes of violence. Today, minorities constitute only a fraction of Pakistan’s population, many having migrated or retreated into vulnerable enclaves in search of safety and survival.

Early Years (1947–1956): Unfulfilled Assurances

Muhammad Ali Jinnah’s August 11, 1947 speech articulated a vision of equal citizenship regardless of faith. However, this vision was never fully translated into state policy. The Objectives Resolution of 1949, which declared sovereignty to belong to Allah alone, laid the groundwork for future constitutional and legal exclusions.

Partition-era violence disproportionately affected non-Muslims. Hindus and Sikhs—who made up roughly 23–25 percent of Pakistan’s population at independence—faced mass displacement, property confiscation, and intimidation. In Sindh alone, nearly a million Hindus migrated within two years. The minority crisis, therefore, emerged at the very birth of the state.

Military Rule and Selective Modernization (1958–1971)

The Ayub and Yahya periods brought economic and administrative reforms but did little to protect minority rights. Subtle constitutional changes weakened guarantees of religious freedom, while communal violence—particularly against Hindus in East Pakistan—intensified.

The 1971 war proved catastrophic for minorities. Hindus were explicitly targeted during the Bangladesh conflict, leading to mass killings and displacement. By the early 1970s, minorities in West Pakistan had dwindled to approximately three percent.

Legal Exclusion and Islamization (1972–1988)

The 1974 constitutional amendment declaring Ahmadis non-Muslims marked a critical shift toward state-sanctioned religious exclusion. This trend deepened under General Zia-ul-Haq, whose Islamization policies reshaped Pakistan’s legal and social order.

Blasphemy laws, Hudood ordinances, and revised school curricula disproportionately affected minorities. Forced conversions of Hindu girls in Sindh increased, Christian communities faced mob violence and false accusations, and Ahmadis were legally barred from practicing their faith openly. This period institutionalized intolerance within state structures.

Democratic Interludes, Persistent Vulnerabilities (1988–2000)

Despite the return to civilian rule, successive governments avoided reforming discriminatory laws, fearing religious backlash. Attacks on churches and temples continued, while courts often legitimized coerced conversions through questionable testimonies.

Minority communities increasingly withdrew into segregated spaces, surviving through silence rather than protection.

Radicalization and Insecurity (2000–2010)

The post-9/11 period further destabilized minority life. Militant groups targeted Christians, Hindus, Sikhs, and Ahmadis with relative impunity. Incidents such as the Gojra massacre (2009) highlighted the deadly consequences of unchecked extremism.

Migration accelerated as minorities sought refuge abroad, hollowing out historic communities across Pakistan.

2010–2025: Shrinking Space, Deepening Fear

In recent years, blasphemy accusations have multiplied, often used to settle personal disputes or seize property. The assassination of Punjab Governor Salman Taseer in 2011 underscored the growing power of extremist narratives.

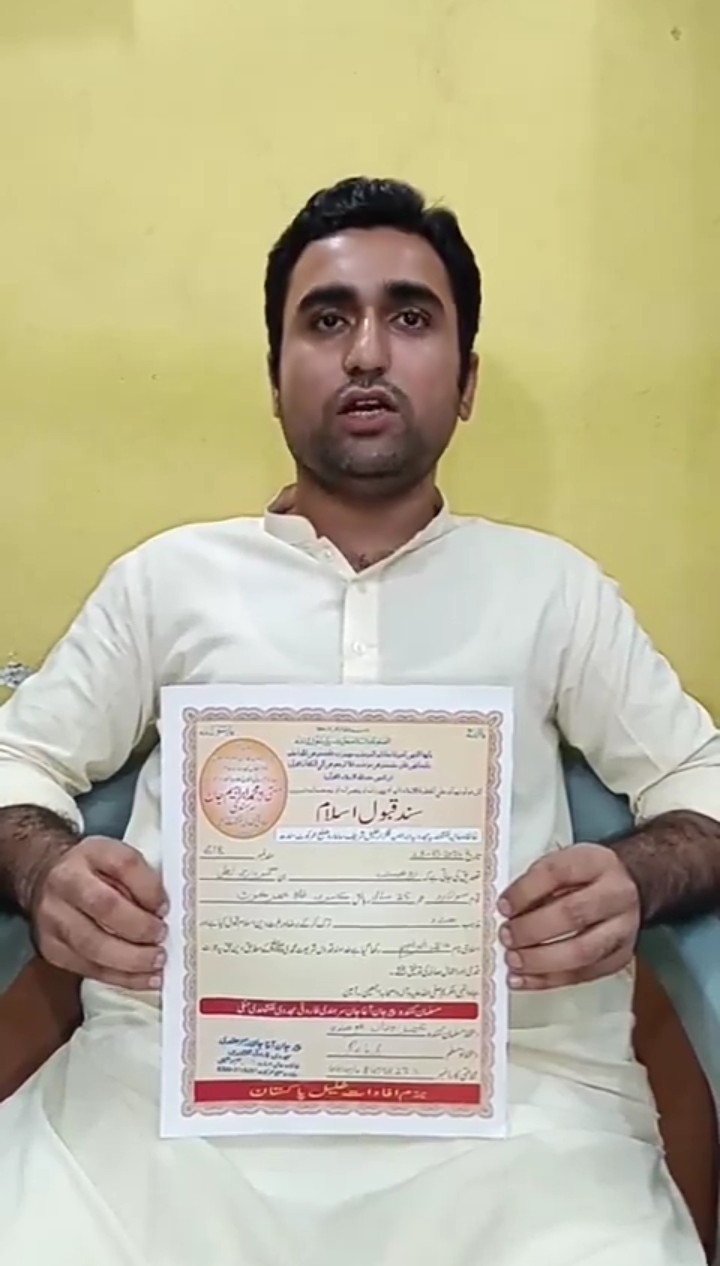

Forced conversions- particularly of Hindu and Christian girls—remain widespread, especially in Sindh. Ahmadis continue to face systemic exclusion through segregated voter lists, mosque closures, and criminalization of religious expression.

By 2025, minorities make up just 3–4 percent of Pakistan’s population- a dramatic decline from independence.

Where Have the Minorities Gone?

This demographic collapse is not accidental. It reflects decades of:

-

Discriminatory legislation

-

Weak law enforcement

-

Forced conversions and marriages

-

Economic marginalization

-

Judicial failures

-

Persistent social hostility

The cumulative effect has been continuous migration, social withdrawal, and demographic disappearance.

Conclusion: A Moral and Historical Reckoning

From 1947 to 2025, Pakistan has gradually transformed from a multi-religious society into one where minorities exist largely at the margins. Their decline is not merely a statistical trend but a profound moral challenge—raising questions about citizenship, justice, and the country’s constitutional promise.

The story of Pakistan’s minorities is, ultimately, a test of the nation’s conscience. Whether this trajectory can be reversed depends on legal reform, political courage, and a renewed commitment to equal citizenship—before the remnants of Pakistan’s plural past vanish entirely.